The idea behind an eco-philosophic ‘anti-expedition’ to Tseringma (7034 m) came up in the spring of 1969, when professor of philosophy, Arne Naess, and his assistant Sigmund Kvaloey Setreng were camped at Nagarkot (2195m), not far from Kathmandu. They were relaxing after an odyssey of a drive by car from Oslo, Norway, to Varanasi, India, to attend a conference on Gandhian non-violence philosophy. From the vantage point of the former hill station the Himalayan giants from Annapurna (8091 m) to Chomo Langma (8848 m) – also known in the Western hemisphere as Mont Everest – appear as a breathtaking panorama. With his experience from high altitude mountaineering since leading the Norwegian expedition to Tirich Mir (7700 m) in1950, Arne’s attention was soon drawn towards the grand massive of Gauri Shankar (7134 m). This impressive mountain was once recognized as the highest mountain in the world, probably because it dominates the view from the vicinity of the capital. Although it has lost this status, it holds a prominent position in Hindu as well as Buddhist culture as the abode of worshiped deities.

To ‘The people, who came from the East’ – the Sherpas – living in small villages at the foot of the snow covered holy mountains of Himalaya, Gauri Shankar is the most sacred. In their language it is known as Tseringma. Before leaving Nagarkot Arne and Sigmund had become aware of the renowned friendliness of the Sherpas towards fellow humans and free Nature while studying the Tibetan Buddhist philosophy behind their admirable way of life. They concluded without hesitation that they had to return to Nepal as soon as possible to get in touch with the remarkable Sherpas in the foothills of Tseringma, 3700 m above sea level, and enjoy the marvellous rock and ice on a mountain of such symbolic importance, as well as studying a culture without counterpart in its relationship towards free Nature (free Nature: having the seasonal, diurnal and growth rhythms unimpaired).

Sigmund and I were college mates with mutual fancy for jazz and mountaineering. Thus he turned up to enthusiastically share experiences from his Asian odyssey soon after returning home. It was music in my ears when he told about the vision of an encounter with the Sherpas of Rolwaling and enjoying the rock and ice without touching the sacred summits of Tseringma. Since I had left my position as a research officer in biochemistry and microbiology in 1967 and become a full time professional in mountaineering as the leader of one of Europe’s first schools for the practice of ‘steep land art’ in the friluftsliv tradition. I was ready to leave at short notice! But severe threats towards our beloved mountain landscape at home urged Sigmund and me to give priority to help organize a campaign to defend the 4. highest free falling waterfall in the world with its adjacent waterways. Arne followed an invitation to work and lecture at the University of Berkeley.

When the tree member’s small Tseringma Pilgrimage 1971 left for Kathmandu in early September our preparations had been the best. Sigmund had been the leading activist behind the non-violent action to defend Mardoela against damming, according to the philosophy of Gandhi and further development of the rudimentary beginnings of ‘ecophilosophy’ – a way of arguing for the inherent value of free Nature – the very beginning of which was established under the Arctic Tower of Stetind (1392 m) in 1966 by the philosopher Arne and at that time the engineer Nils, drawing on an early introduction to ecology during a stay at a German technische Hochschule 1958 – 59. Arne contributed essentially to prepare us for what we chose to call the Tseringma Pilgrimage with his thorough study of Buddhist philosophy and Sherpa culture, obtaining support from a German research foundation in Nepal and permission for visiting a restricted area. My contribution was among others to care for the complete equipment, including the construction of special gear for high altitude camping and mountaineering, which was not in stock at shops these days. I had also been an active partner in the further development of ecophilosophy as a lay-out for a nature friendly future and the concept of an ‘anti-expedition’.

To practice the concept of an ‘anti-expedition’ was our chosen way of raising a protest against the pressure on free Nature and the Sherpa culture caused by the heavy, army-like expeditions, which had been intruding pristine regions in Himalaya since the 1920ies. Hundreds of ill equipped porters, along with the luxuries kitchen services for the sahibs, dependent on taking firewood in exposed tree line areas, made a damaging effect. The social impact of such invasions also strongly impaired the cultural patterns of small Sherpa villages and at times more or less depleted the rations, which with much effort had to be harvested in steep and far away places. The most serious was – and still is – the impact on the religious life, the loss of workforce due to the men in the villages taking part in the expeditions – and some times the loss of indispensable family supporters in mountain accidents.

As mountaineers we were deeply critical to the offence against the Alpine Club’s gentlemen contract of mountaineering by fair means in Himalayan nationalistic, victory-driven attacks on mountains, of which many has been worshipped as sacred. Our eight day trek to the village Beding at the foot of Tseringma, led by sirdar Urkien with many years experience from expeditions for scientific and mapping purposes, had only eight porters – all of them at home in Rolwaling and equipped in their traditional way. Two of Urkien´s neighbours in the Khumbu valley and trusted expedition helpers, Pasang and Lachpa, came with us to be our rope mates – not high altitude porters! They were our cooks though, when we were all together in the same camp, so that we could enjoy true, vegetarian Sherpa meals – we had of course brought the food for our pilgrimage from the abundance of the Kathmandu valley. From home we of course brought fish and geitost (caramelised milk sugar – an exquisite ‘up hill food’ from Norway).

We of course avoided any safari equipment. We had consequently and carefully selected lightweight mountaineering gear for our small camps and for alpine style climbing. To be able to follow Arne’s old concept of climbing for the joy of discovering and not for ‘attacking’ the summits, I ran a course in alpine climbing for Pasang and Lachpa on rocks near the village, so that they could be complete rope mates, handling at that time nature friendly and state of the art equipment like Sticht rope brakes and the English nuts (a metal wedge threaded on a wire) for protection. We brought pitons for icy conditions, but not to be used for fixing ropes, as it was our firm intention to demonstrate a new approach to mountaineering in the Himalayas, any sort of technical aids were incomprehensible. In agreement with the Lama of Beding, Yelung Pasang we set the limit for our climbs to an altitude of about 6000 meters.

Sigmund was our liason with the Lama, who demonstrated his faith in him by inviting him to study and sleep in the monastery next to the monastery cell of Yelung Pasang himself. Thus Sigmund with the help of Pasang as an interpreter had frequent dialogues with an exceptional representative of Tibetan Buddhism after his some 40 years in Tibetan monasteries. Sigmund gave priority to making acquaintance with Sherpa families to take part in their every day life. He also followed the celebrations of Buddhist rituals, whereas Arne and I spent most of the time in close contact with Tseringma. When all tree of us met every now and then in Sigmund’s study to elaborate on our versions of the fusion of the natural science of ecology and the philosophical keel and rudder – values orientation – for an ecophilosophy, Arne and I were pleased to learn about Sigmund’s research into a living Sherpa culture.

After Arne had spent a couple of weeks in physical and mental dialogue with Tseringma, he unfortunately fell ill and thus he could not follow us on a 6 day trek over the Tesi Lapcha (5755 m) Pass to the Khumbu valley and the home village of Pasang and Lachpa. We decided to do the best out of the new situation and use Arne as ‘post runner’ – the way Himalayan expeditions used for communication before electronic equipment took over – to bring a petition for a ban on permission for summit climbs on Tseringma and other holy Himalayan mountains according to Buddhist belief. Sigmund in his role as a liason, arranged for a village consultation in the open in front of the monastery. Following introductory remarks by the Lama the villagers unanimously signed the petition, which was addressed to the King of Nepal – at that time still in office.

After Arne left, Sigmund also joined us climbing and having the privilege to work on patterns of thought for a nature friendly future in a literally breathtaking camp in the lap of Tseringma, as Sigmund put it. But after unforgettable days and starry nights the time came to move on as winter was approaching. Our trek over the Tesi Lapsha Pass to Thame with one of the oldest monastery Khumbu and visit in Kumjung added new dimensions to our pilgrimage. The trek was in itself grandiose. In the village Thame Sigmund’s encounter with the Lama resulted after later visits to his status as a lama. The strongest impressions we got from Pasang and Lachpa’s village Kumjung was the impact made by the construction of the hotel Mount Everest View and an airfield to be established in the best potato fields of the village. We were lucky to be present at a day, when Edmund Hillary was applauded for establishing a Hillary-school – with a tin roof (!) – and to walk with Sir Edmund down the Khumbu valley. Half way down the path to Namche Bazar we hit upon Hillary’s rope mate, when they reached ‘The third Pole’ – Tenzing – who by the way was born in Thame.

Back home we were deeply moved by a once in a life time experience and eager to work out the experiences and share with our countrymen as well as mountaineers and people looking for new ideas for å greening of the world – not only America, which was a title of a book on sub-cultures appearing in USA 1970. Sigmund’s one hour TV documentary was a vivid presentation of our pilgrimage and a powerful introduction to ecophilsophy and ecopolitics, which was strongly influenced by our encounter with the nature remarkable Sherpa culture.

We used the film for our lectures and seminars, as well as my photographs. Sigmund returned to Sherpa country over and over again, expanding his ecophilosophical and ecopolitical work in a jazz-inspired improvisation in the spirit of the Norwegian folk tail hero Askeladden, following Gandhi’s lead: Seek conflict to expose and settle by no-violence unacceptable situations. Thus he ceaselessly challenged the ‘industrial-economic growth modernity’ in a manifold of ways till at last an heart disease slowed him down.

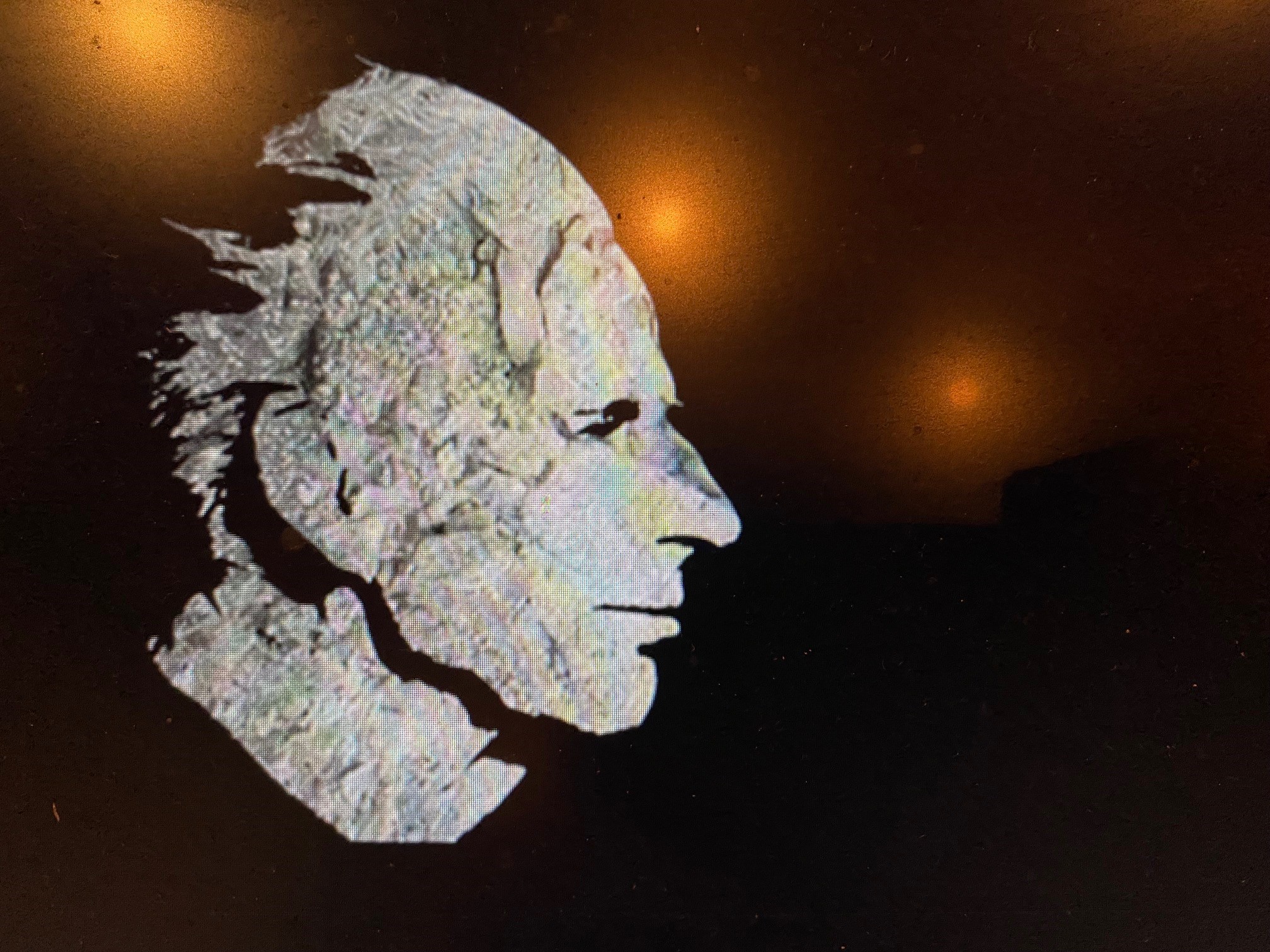

Arne’s encounter with Sherpas live during the Tseringma Pilgrimage 1971 and the opportunity to study Sherpa traditions and Sherpa/Tibetan Buddhism in medias res influenced his philosophy of wisdom, supported by the natural science ecology, markedly. We are grateful for his change of focus in his work towards ecophilosphy. His enduring efforts for this new field resulted in an international discourse with participants from all continents. A talk he gave in Bucharest in 1972 at the Third World Future Research Conference, where he argued for ‘deep ecology’ – a forerunner for his ecosophy – is considered to be the first international presentation of ecophilosphy.

Sigmund and I did not share Arne’s belief in changing the culture of modernity by means

of philosophical arguments alone. Having worked for six years already with inspiring encounters with free Nature in the Norwegian and Alpine tradition towards a change of values orientation, I brought back learning practices in the home of culture – free Nature – with a lasting effect. This has been the backbone of the learning processes we call conwaying for professionals of most branches in modern societies, as well as for individuals who are in search of deep acquaintance with free Nature to enable a nature friendly career and/or for the joy of the encounter.

The Tseringma Pilgrimage 1971 along with the Mardoela non-violent action did make a difference in a greening of Norway in the 1970ies in the change of patterns of thought, in politics, in learning processes and social organization. Then the oil-era happened and a blossoming spring changed into an early autumn. The seeds are there and the grass roots show signs of spring. A change for a nature friendly future is forthcoming as soon as the signs of spring we are able to create are so many that they coalesce in a spring thaw.

I love what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and

exposure! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve added you guys to

blogroll.

Thanks for writing this incredible piece. I have been working with Bob Henderson on his new book about your ‘anti-expedition.’ I appreciate how far ahead of the curve you all were in seeking greater meaning out of the mountains and cultures we travel through. My chapter in the book deals with the idea of travel. I have really enjoyed writing it and have pondered how the idea of anti-expedition fits into my world view. I am a professor at Souther Oregon University and teach Outdoor Adventure and Expedition Leadership. I look forward to bring the idea of ‘anti-expedition’ up with my students.

Cheers,

Chad